Early last March, the chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee recommended that Republicans stop holding town hall meetings, after several confrontations with angry attendees went viral. One senator not to heed that advice was Iowa’s Joni Ernst. On May 30, 2025, Ernst held a town hall in Parkersburg. She attempted to set the ground rules for participation shortly after she was introduced: those with questions got their names into a queue (apparently compiled in advance), and when it was their turn they were presented with a microphone held by one of two aids. This, obviously, is a way of limiting who can speak, and how long they can speak for.

The audience was not content to remain quiet, however, and collective shouting erupted at several junctures. Sometimes Ernst ignored this, or repeated her words once it had subsided, but on a number of occasions she responded to audience members whose shouted comments stood out above the din. On one such occasion she responded with a seemingly heartless comment that quickly went viral.

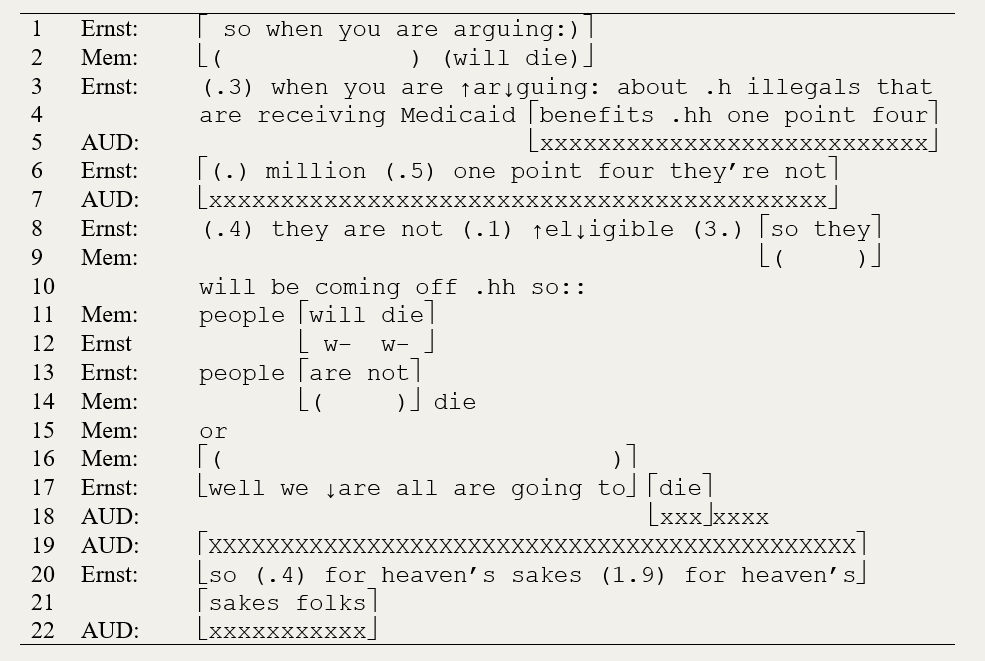

At the top is a short video of highlights. (Here is the full video. The advantage of the shorter video is that it offers a better close-up of the senator.) The key exchange, starting at 45:05 of the long video and 9:46 of the short one, is roughly transcribed below. General audience shouting is represented by multiples of the letter “x,” in lower case or capitals depending on its volume. “Mem” (as a speaker) means some member of the audience whose voice stood out, often because they were alone in shouting at that moment. Partial square brackets indicate overlapping talk. Arrows represent changes in intonation and pauses are in parentheses, timed to the tenth of a second. Inhaling is indicated by .h or .hh (depending on its length) and colons indicate a stretched sound. (E.g., “so::” in line 10 might also be transcribed as “soooo”.) (For reference, all transcribing conventions are explained here.)

The immediate context for this was a queued question about how the House’s spending bill would cut funding to Medicaid and SNAP (food stamps). In lines 1, 3-4, 6 and 8, Ernst says that it is the “illegals” who will lose benefits. The audience beings shouting in the midst of this, in line 5 (overlapping with part of line 4) and line 7 (overlapping with all of line 6). In line 8, Ernst restarts her sentence about eligibility once the shouting subsides, speaking in a slightly condescending tone.

In line 11, a member of the audience—not someone in the queue—shouts “people will die!” Ernst, who was faintly trying to speak at the same time, responds. “People are not–” she begins, before interrupting herself. Given her dismissive tone, I think she was going to say “people are not going to die,” but catches herself and instead says “well, we are all going to die,” which earns her a period of loud jeering.

Ernst’s aborted response in line 13, and its substitution in line 17, is known as self-correction or self-repair (Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks 1977). We do this when we realize we are about to make a mistake of some kind, and here it is likely that Ernst realizes that it would be foolhardy to deny that people die, or more precisely that illegal immigrants denied healthcare will die as a direct consequence of that. What’s interesting is what she puts in its place. “Some of them may die” would be more defensible but would seem callous. “We are all going to die” also seems calloused, but takes the focus off of “illegals” and her responsibility for their lives or, for that matter, anyone else’s.

Someone suggested to me that Ernst is revealing an Ayn Rand ethic here, in which the inevitability of death is accepted, along with our lack of responsibility for helping others. This hearkens back to something she said a bit earlier, that the federal government was founded “for those things that the people could not do for themselves,” like provide for a common defense and settle disagreements—a job list that didn’t include the centralized provision of healthcare. Yet, Ernst did not generally sound heartless, expressing her appreciation for community health centers and the “most vulnerable” (assuming they are in the country legally), and empathizing with someone burdened with the high cost of nursing home care for a parent.

Ernst was embattled during this meeting, and mostly responded to difficult questions by changing the subject. Here she did not, though she was entitled to ignore the question altogether as it did not come from someone properly in the queue. But to this accusation, that “people will die,” there seems to have been no good answer once she committed herself to providing one.

Cited

Schegloff, Emanuel A., Gail Jefferson, and Harvey Sacks. 1977. “The Preference for Self-Correction in the Organization of Repair in Conversation.” Language 53 (2): 361-82.

Leave a comment