A few weeks ago, this video of Australian twins Bridgette and Paula Powers went viral. (I recommend watching it.) In it, the twins recount a carjacking that they witnessed while at work, delighting viewers with their seemingly unison delivery. Jimmy Kimmel had them Zoom into his show and they remained true to form. Saturday Night Live spoofed them, though the spoof could hardly match the original.

The obvious question is: how do they do this?

Gene Lerner has written about how people can finish one another’s sentences. One does this by monitoring the speaker’s turn-in-progress for clues to where it’s heading and then interrupting to finish it, or at least to offer a candidate competition (Lerner 1996). In one variation of this, the two speakers finish the sentence together, “chorally,” using the same words (Lerner 2002).

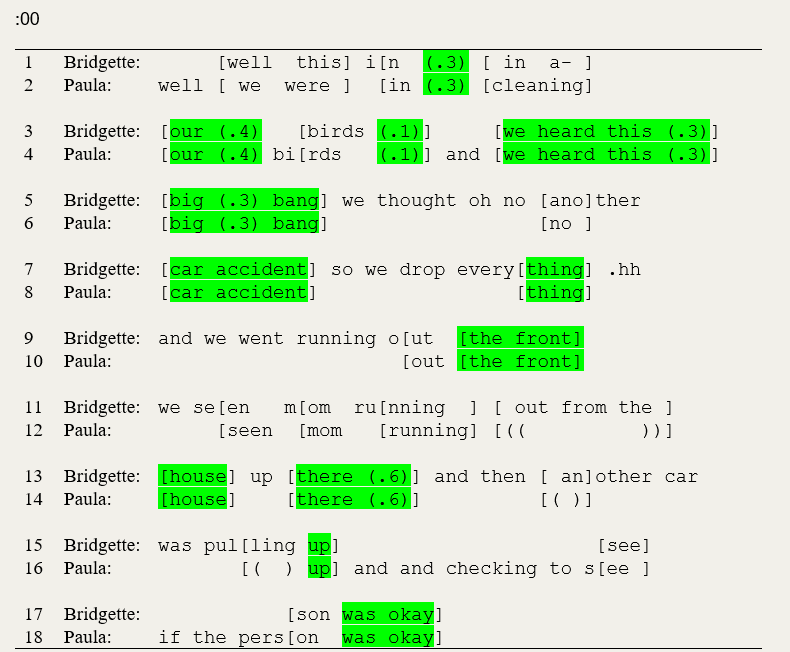

Below I’ve transcribed the first twenty-five seconds of the video, as best as I could without spending the whole day on it. The format of the transcript is a little unconventional. As usual, brackets indicate overlapping talk, but I used green highlighting to indicate when the two were perfectly in unison or very nearly so. Pauses are timed to the tenth of a second and contained in parentheses. Empty parentheses refer to talk that could be heard but not deciphered. (All the conventions are explained here.)

One thing we see is that the two are only perfectly in sync a few times. The rest of the time, either only one is speaking or one is lagging slightly behind. Assuming the twin on the left is Bridgette and the one on the right is Paula, as suggested by the video, Bridgette leads for most of these twenty-five seconds, but then, in lines 15-18, it is Paula’s turn.

The sisters speak at a very even and relatively slow pace, almost as if to a metronome, which surely facilitates this coordination. They also presumably have a lot of practice at this, sharing and thus easily recognizing vocabulary and turns of phrase, and of course, they are relating events that they both saw and most likely have already recounted at least a few times together.

Most importantly, this is something they are obviously trying to do, with the lagging sister visibly trying to join up and neither desisting upon finding themselves speaking in overlap though this is what people normally do in that circumstance.

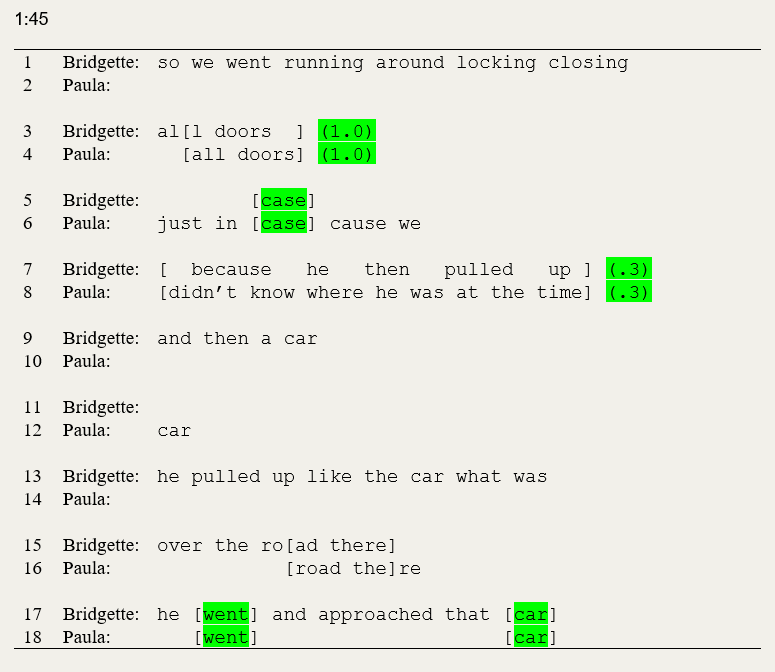

Here’s another clip, from a bit later.

Again we see that they are only occasionally in unison, with Bridgette joining in just in time to say “case” with her sister in lines 5-6, while it is Paula who is lagging behind in lines 3-4, 15-16, and 17-18. Interestingly, they go their separate ways, briefly, in lines 7-8. They then both stop at the end of their respective sentences, pause in unison, and then it is Bridgette who continues in line 9 and then leads the way for the remainder of the excerpt.

Cited

Lerner, Gene H. 1996. “On the ‘Semi-Permeable’ Character of Grammatical Units in Conversation: Conditional Entry into the Turn Space of Another Speaker.” Pp. 238-76 in Interaction and Grammar, edited by Elinor Ochs, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Sandra A. Thompson. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

—. 2002. “Turn-Sharing: The Choral Co-Production of Talk-in-Interaction.” Pp. 225-56 in The Language of Turn and Sequence, edited by Cecilia E. Ford, Barbara A. Fox, and Sandra A. Thompson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leave a reply to Anna Gabur Cancel reply