On January 7, 2026, President Donald Trump conducted a two-hour interview with four reporters from the New York Times. The full transcript is here, though, so far, only a few excerpts from the audio recording have been released. (Some are assembled in the YouTube short above.)

Many have looked to this for clues about Trump’s view of world, including the constraints placed on him, or not, by international law. On his Substack, for instance, Michael D. Sellers describes it as “a sustained exposition of how Trump now understands presidential power.”

Sellers’ analysis is insightful and grounded in the interview transcript, though you have to look past Trump’s many digressions about Sleepy Joe, the stolen 2020 election, and the strength of our military (for which Trump repeatedly claimed credit) to call this “sustained.” It’s a little bit like playing connect-the-dots by ignoring a lot of the dots.

From the perspective of language-in-interaction, there are many points of interest, including the journalists’ willingness to interrupt the president, their competition with one another to pose and press questions, and the way in which they alternated between challenging Trump’s version of events (in particular, the killing of Renee Good) and holding back.

I like a recording, however, because I distrust transcripts. One problem with transcripts is that those linearize speakers so that it’s hard to know when people were actually talking over one another. Another is that transcribers regularly add or remove words to improve readability, making speakers out to be more grammatical and fluent than they actually were. In extreme cases, that means attributing positions to people that they did not take because someone thought that’s what they meant to say. I discuss some of these problems in an article on (of all things!) minute-taking (Gibson 2012).

Another thing transcripts usually omit is information about prosody, including intonation and volume. Here I want to focus on Trump’s intonation in two of the exchanges that drew the most attention, pertaining to his lack of restraint when it comes to military action, as exemplified by the attack on Venezuela and the seizure of its president, Nicolás Maduro, only a few days earlier.

“Intonation involves the occurrence of recurring pitch patterns, each of which is used with a set of relatively consistent meanings,” writes Cruttenden (1997: 7). What Cruttenden really means is that the study of intonation takes as its premise that such meanings can be isolated from specific utterances. Success at isolating that meaning has been, I gather, modest. Everyone can agree that a sharp rise in pitch (usually on the naturally accented syllable) announces “this word is especially important!”; that questions often (but not always) end with rising intonation (Geluykens, 1988); and that falling intonation at the end of a sentence means that the speaker is ready to relinquish the floor (Walker, 2013). But the meaning of the “tune” played over a longer stretch of words is harder to nail down though we often sense there is one. Cruttenden opines that some tunes make the speaker sound “condescending,” “gentle,” “serious,” “business-like,” “grumbling,” or “soothing” (1997: 8, 49, 51, 55).

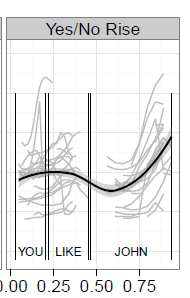

That all sounds pretty impressionistic and I worried that Cruttenden is dated so I went looking for something more recent. In 2015, Daniel Goodhue and colleagues published a conference proceedings paper entitled “Toward a Bestiary of English Intonational Contours.” As it turns out, their bestiary is pretty meager, like a “zoo” I once went to that had some goats and a fox. Even so, they provide evidence of recognizable intonational contours associated with incredulity, contradiction, and what they infelicitously call an “incomplete response,” which might be better called “reminding.” Here, for instance, is how subjects tended to read the sentence “you like John” when the circumstances called for incredulity, which is also what they thought conveyed incredulity when they heard someone else read it:

This is a computer-generated graph of rises and falls in voice pitch. (More technically, it graphs the fundamental frequency through time.) Individual speakers are in grey and the average is in black (though this gives the false impression of continuous vocalization whereas it looks like all of the speakers inserted a gap between “like” and “John”). Basically, there’s slightly rising intonation on “like,” and an abrupt drop on the start of “John” whereupon it sharply rises over the course of that name. In the CA notation I use, this would be written as you like↑ (.) ↓John↑↑—which definitely is not as precise.

There’s been some research on Donald Trump’s prosodic predilections specifically. Summarizing this, Kjeldgaard‑Christiansen (2024: 293) writes that, “[a]s against the formal rigidity or robotic monotonicity of ‘the politicians,’ Trump employs a dynamic prosody that evokes an excitedly informal, conversational tone,” both in speeches and in interviews.

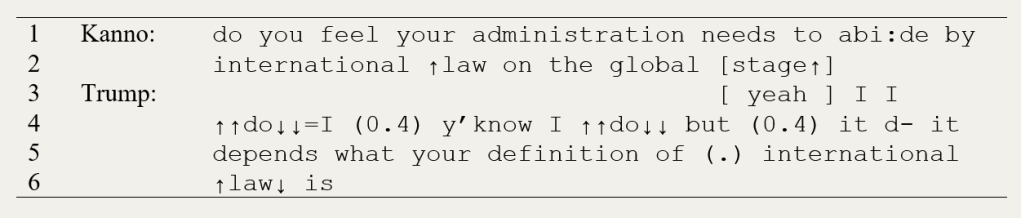

Now for the Times interview. Two comments caused particular alarm. I consider these in reverse order because the second one is easier to explain. Here it is, as an audio clip, conversation-analytic transcript (conventions are explained here), and pitch contour (by Praat):

White House correspondent Zolan Kanno-Youngs asks Trump if he feels that he needs to abide by international law. “Yeah I I ↑↑do↓↓ I (0.4) y’know I ↑↑do↓↓,” the president replies, intonationally stressing both instances of “do,” which typically communicates an attempt to correct a presupposition; here that would be that he is indifferent to international law. There are two problems with this interpretation, however. First, the wording of Kanno-Youngs’ question anticipates an affirmative answer, by basically stating it and then asking for affirmation (e.g., Raymond & Heritage, 2021). Second, the discourse marker “y’know” says outright that his answer will not surprise the reporter (Schiffrin, 1987: 267-295). This might just be filler, but if we take it seriously the overall message seems to be: This is something you know, or should know, but it might surprise other people.

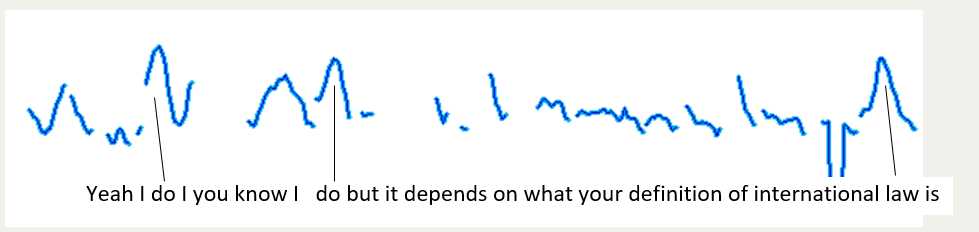

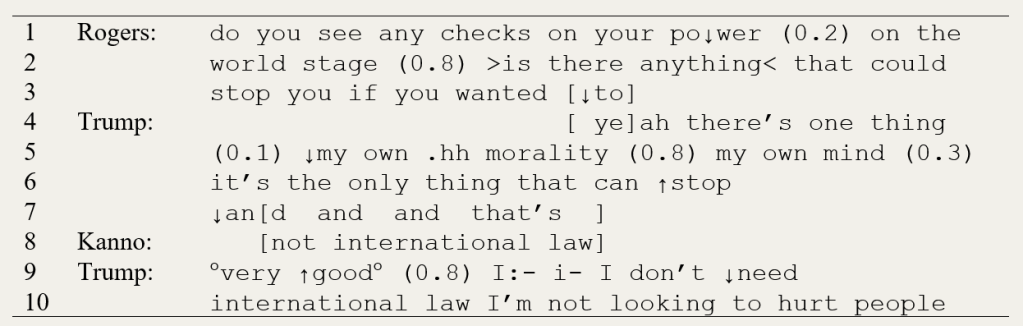

More puzzling (and to many commentators, alarming) was Trump’s response to another question asked a moment earlier by correspondent Katie Rogers:

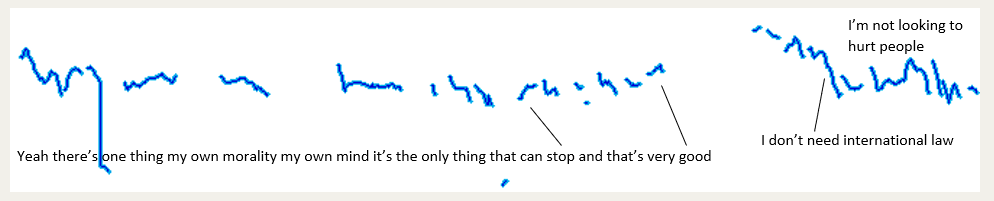

In lines 1-3, Rogers asks if Trump feels that there are any “checks” on his power on the “world stage.” Trump’s response: “yeah there’s one thing (0.1) ↓my own .hh morality (0.8) my own mind (0.3) it’s the only thing that can ↑stop ↓and and and that’s °very ↑good°.” What’s striking about this, apart from the content, is the mostly flat intonation, communicated only imperfectly by the pitch contour (so it’s important to listen to the audio).

What should we make of this flat intonation, which rises only very slightly on “stop” and “good”? I’ve been thinking about this for weeks now and have run it past several students and colleagues. One possibility is that this is a feature of Trump’s idiolect—his personal way of speaking. (We all have one, though conversation analysts are loathe to resort to this as an explanation.) Another is that it indicates some kind of mental state or cognitive operation, such as a lack of interest or investment or that he’s thinking about something else. A third is that he is repeating something he heard from his advisors without having much personal investment in it.

In fact, it’s hard to find any study of flat intonation, almost as if scholars of prosody don’t think that a monotone utterance lacks any features that need explaining. The impression this makes on me (in the spirit of Cruttenden) is one of quiet revelry or self-admiration, which needn’t be accented because he is stating the obvious rather than having to persuade anyone or correct some incorrect presupposition. This is reinforced by the low volume in which he says “very good,” indicated by degree signs (°) in conversation analysis.

In the midst of his answer, Kanno-Youngs attempts to interrupt (which seems pretty nervy): “not international law.” In the pitch contour graph, his voice and Trump’s are impossible to distinguish, but his delivery is also flat, as if seeking confirmation of something he already suspects. When Trump responds, the pitch of his voice has jumped, and falls on “need.” Here, the impression I get is one of dismissiveness.

Someone observed that Trump frequently employs flat intonation, which sent me looking for more examples. The best one I came across (when my wife walked by listening to the radio on her phone) is from an NPR segment a few days ago, when he answered a question about the Kennedy Center, now closed for “renovations” (in the face of plummeting ticket sales and a scramble for the door by a large number of scheduled artists). Here’s the clip:

“The ↑Ken↓nedy Center’s gonna be incredible .hhh within (1.1) ten months,” he says, “>I mean you’re gonna see we’ve ↑already done< tremendous amounts of work but .hh within ten months you’re gonna see <something that you (.1) really be (.5) a↑mazed ↓at.” Most of this is intonationally flat, and the rise on the second syllable of “amazed” is hardly noticeable except in contrast to that. To me, this sounds noncommittal, as if he has to say something to justify closing the Center and defaults to big promises that might not materialize. But it may, once again, reflect a kind of quiet self-admiration.

This is all pretty inconclusive, and I welcome input from anyone more schooled in prosody. But there is a good reason that Trump’s intonation is hard to explain, absent a much larger study on flat intonation. In conversation analysis, when we venture a hypothesis about what a particular practice accomplishes, and what it was meant to accomplish, we look to immediately subsequent talk for support. For example, evidence that intonation conveyed flippancy would be evidence that the immediately next speaker acted as if something flippant had been said. However, this far into the Trump era, everyone has learned to take his words both seriously and literally, which is why these have been quoted so extensively by the press, and why Michael Sellers can look to his words for clues as to his view of the world and his place in it, without concern for how he delivered those words. Maybe Trump was improvising, maybe he was joking, maybe his mind was wandering, maybe he was in awe of himself. (What I don’t hear is cognitive impairment, which will annoy some readers.) But when a president says something, it’s irresponsible to dismiss it because of how it was said or what else it was mixed in with. And that’s especially true of this president, however much he seems to be shooting from the hip.

Cited

Cruttenden, A. (1997). Intonation (2nd edition ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Geluykens, R. 1988. On the Myth of Rising Intonation in Polar Questions. Journal of Pragmatics 12(4), 467-485.

Gibson, D. R. 2022. Minutes of History: Talk and its Written Incarnations. Social Science History 46(3), 643-669.

Goodhue, D., Harrison, L., Siu, Y. T. C. e., & Wagner, M. (2015). Toward a bestiary of English intonational tunes. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 46th Conference of the North Eastern Linguistic Society, Concordia University.

Kjeldgaard‑Christiansen, J. 2024. The Voice of the People: Populism and Donald Trump’s Use of Informal Voice. Society 61, 289-302.

Raymond, C. W., & Heritage, J. 2021. Probability and Valence: Two Preferences in the Design of Polar Questions and Their Management. Research on Language and Social Interaction 54(1), 60-79. 10.1080/08351813.2020.1864156

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse Markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walker, G. (2013). Phonetics and Prosody in Conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (1st ed., pp. 455-474). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Leave a comment