On September 4, 2025, Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. appeared in front of the Senate Finance Committee to answer questions (and receive accusations) about his vaccine policies and turmoil at the Centers for Disease Control. Some Republican senators came to his defense or asked softball questions. Others, including Republican Senator Bill Cassidy and several Democratic senators, sharply challenged him, often leaving him little opportunity to respond (due to time limits on each senator’s turn at bat). Still others, including Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, were mainly concerned to voice state-specific concerns and to press Kennedy to publicly promise to act to address those.

Several senators pressed Kennedy about the firing of CDC director Susan Monarez, after she refused to resign when pressured to do so. First to do so was Oregon Senator Ron Wyden. Second to do so was Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren. In responding to Warren, Kennedy made the claim that he asked Monarez to resign after the latter announced that she was not a “trustworthy person.” Surprised, Warren replied that this contradicted Monarez’s own account in an op-ed published that morning in the Wall Street Journal.

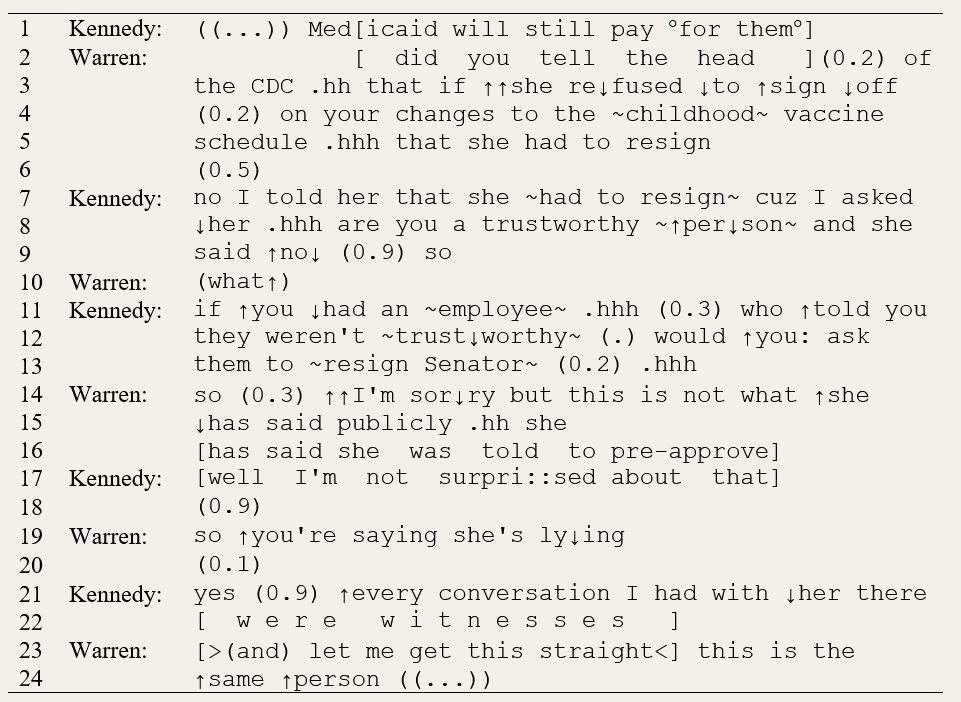

This provides for an interesting study in what scholars of language called “reported speech” (e.g., Holt 1996)—and one particularly poignant to me, given all the time I spent listening to Kennedy’s father and uncle (JFK) for my book on the Cuban Missile Crisis (Gibson 2012). The exchange, which starts at the 2:05:00 mark of the above video, is transcribed below (accompanied by the audio clip). (Transcribing conventions are explained here.) What is most interesting is how Warren simplifies Monarez’s account to make it unacceptable to Kennedy, and how this puts him in the position of either disputing Warren’s reading of the op-ed or disputing the account attributed to the former director when Warren asks if he is accusing her (Monarez) of lying.

Prior to the start of the excerpt, Kennedy and Warren had been arguing about whether anyone who wants a COVID booster would be able to get one. Kennedy repeatedly said that they could, but as Warren pointed out, that the vaccine was not approved FDA for most adults was an impediment, partly due to uncertainty about whether insurance companies would pay for it. In line 1, Kennedy is finishing his claim that Medicare and Medicaid would pay for the vaccine. Warren, already done with this line of questioning, talks over him in order to pivot to Monarez, resulting in a period of overlapping talk from which neither immediately backs down. Once in the clear, Warren continues to ask whether Kennedy gave Monarez an ultimatum to either sign off on the changes to the childhood vaccine schedule or resign, without identifying the provenance of this account (lines 2-5). In lines 7-9, Kennedy responds in the negative, offering his own version of what happened, in which he and Monarez had a conversation that allegedly ran as follows:

Kennedy: Are you a trustworthy person?

Monarez: No.

After Warren expresses surprise or incredulity in line 10, Kennedy asks if she (Warren) would not have done the same in response to such a confession from an employee (lines 11-13). Then Warren, in lines 14-16, identifies her source: Monarez’s own public statement.

Assuming this means the op-ed, it is a slight misrepresentation of Monarez’s account, which was that she was pressured to resign at an August 25 meeting at which she was told to preapprove the advisory panel’s recommendations, not that she was told to resign because she refused. Of course, that’s implied, but it leaves room for an exchange such as the one related by Kennedy, as the intervening and immediately precipitating event for the resignation demand.

Of course, that exchange itself is peculiar, in a way that neither Warren nor Senator Bernie Sanders, who questioned Kennedy next, thought to pursue. Presumably there was a context for the secretary’s question about trustworthiness, something that he asked if could trust Monarez to do, and the two accounts can be reconciled if that “thing” was to preapprove the recommendations.

Obviously, if that is what happened, Kennedy is splitting hairs, in order to justify Monarez’s eventual firing as warranted by her purportedly self-confessed lack of trustworthiness while suppressing the thing she may have agreed she could not be trusted to do. It may also be an appeal to Trump’s conservative supporters, who, we know from the work of Jonathan Haidt, place great value on both loyalty and respect for authority (Haidt 2012). Basically, this little reported conversation paints her as both disloyal and disrespectful of her boss.

To continue with the excerpt, in line 16, Warren says that Monarez said that “she was told to preapprove.” Kennedy is talking at the same time (line 17), and may or may not have heard that, so that when Warren asks if he is claiming that Monarez was lying, it is not clear whether, in saying “yes,” he means that she was lying when she said she was told to preapprove or that her account of the request that she resign was a lie. If the latter, in making this strong accusation he might have been lured in by Warren, who in lines 14-15 posited a contradiction between the two accounts that left little room for “let’s figure out how to reconcile these stories.” Not that anyone was feeling particularly conciliatory, and throughout the hearing, Kennedy’s skeptics seemed more concerned with making accusations than in letting Kennedy respond to them.

We may know more soon, as Monarez is set to testify on September 17 and if the witnesses Kennedy mentions in line 22 speak up.

Sept. 17, 2025 update: Monarez testified today and offered her own account of the crucial exchange, which according to her went as follows:

Kennedy: I cannot trust you (after she refused to approve new recommendations without evidence and fire career officials.)

Monarez: If you believe you cannot trust me, if you can fire me.

Oklahoma Senator Mullin claims, however, that other people who were there allegedly back Secretary Kennedy’s account. (He also claimed there was a recording, which would have resolved this, but later walked that back.) All of this seems like splitting conversation hairs but that is, at least, in the spirit of this blog!

Cited

Gibson, David R. (2012). Talk at the Brink: Deliberation and Decision During the Cuban Missile Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon.

Holt, Elizabeth. 1996. “Reporting on Talk: The Use of Direct Reported Speech in Conversation.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 29 (3): 219-45.

Leave a comment