On December 9, 2023, the presidents of MIT, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania testified in front of Congress about charges of anti-Semitism on their campuses. The grilling went on for more than five hours. The most dramatic (and re-played) moments came at the end, when they were questioned by New York Representative Elise Stefanik, herself a Harvard graduate. Most dramatic of all was her exchange with U. Penn’s president, Mary Elizabeth Magill, transcribed below. This started at 5:04:25.

The presidents were in a difficult position, obligated to provide truthful answers (lest they commit perjury) about their universities’ policies during a tumultuous time on their campuses, in terms of protests and free speech, given the presence of students from, or principally sympathetic to, both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Years ago, Molotch and Boden (1985) wrote about the testimony of John Dean, White House Counsel under Nixon, during the Watergate hearings in the U.S. Senate. One of their arguments is that the power to ask questions and demand responses of a certain sort is the power to shape the version of reality presented to the public. “Through purposive control over the very grounds of verbal interchange, conversational procedures become mechanisms for reifying certain versions of reality at the expense of others, and thus become a tool of domination” (p. 273).

Stefanik’s questioning was effective if the goal was to make Magill (and the other presidents) look bad. She asked polar (i.e., yes/no) questions, and made a show of demanding “type-conforming” (Raymond 2003) yes/no answers, though didn’t actually insist on that. That gave Magill time to provide slightly more nuanced answers, along the lines of “it depends,” but this was just the rope she needed to hang herself with because these afforded Stefanik the opportunity to perform horror, which she did through steadily escalating pitch and, at one point, a quavering voice.

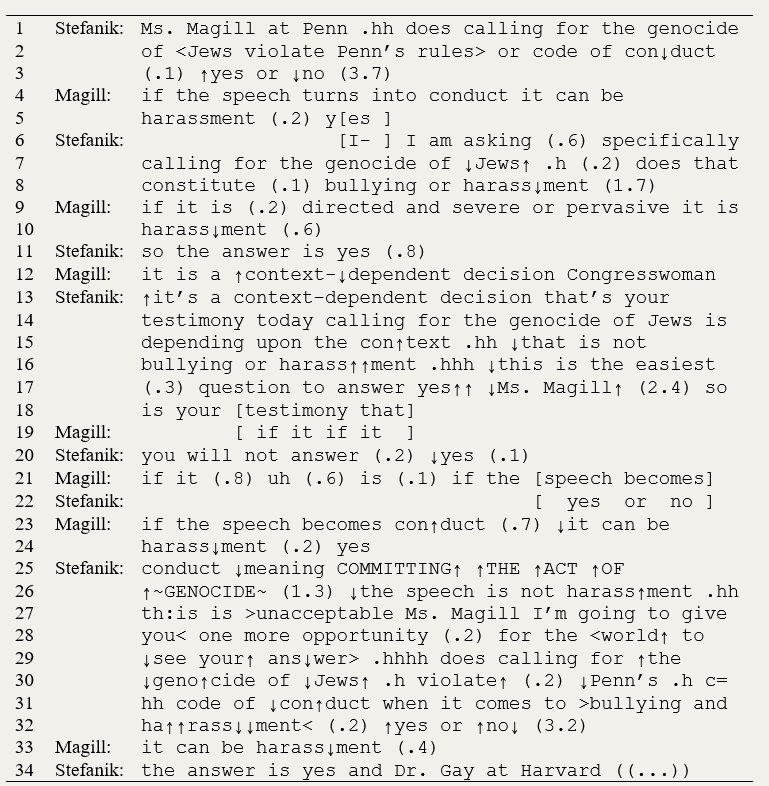

Transcribing conventions are explained here. In lines 1-3, Stefanik asks if “calling for the genocide of Jews” violates “Penn’s rules or code of conduct.” “Yes or no,” she adds. Then there is a very long pause, of 3.7 seconds (in parentheses). This might be because Magill needs to think for a moment about how best to respond, but another explanation is that this adds some space before the yes/no question and an initially nonconforming answer—that is, one that doesn’t offer a “yes” or “no” right off the bat. Eventually there is an affirmative response but only after she states conditions, that the speech “turns into conduct” (lines 4-5). Basically, it seems that the straightforward answer would have been “no,” but Magill finds a clever way to get to “yes.” Stefanik is not satisfied, however, and presses the original question, about the speech itself, though now asks specifically if that would “constitute bullying or harassment” (lines 6-8). After another long pause, Magill provides a different nonconforming answer, that the speech would need to be “directed and severe or pervasive” (lines 9-10).

In line 11, Stefanik offers a proposed paraphrase, or “formulation” (Heritage and Watson 1979), of Magill’s answer: “so the answer is yes.” This is interesting, because in many ways this is the answer that would have serve Magill best in the moment and also from a PR perspective, and Stefanik seems to be tempting her with it. But Magill can hardly embrace it without being accused of misrepresenting Penn’s rules. Instead of taking the bait, Magill says that the question is “context-dependent.” (Her use of Stefanik’s title at the end of line 12 is curious—no one would have doubted whom she was addressing—but we’d need more data to speculate about what work that does here.)

Stefanik’s voice begins rising (indicated by upward arrows) in line 13 and though it occasionally drops a bit in the course of this speaking turn (lines 13-18), its overall trajectory is up. This communicates indignation and shock. In line 13 she quotes Magill verbatim, keeping attention on the very legalistic phrase “context-dependent.” At the end of her turn she berates Magill for her failure to reply appropriately to “the easier question,” now using the president’s name. Stefanik pauses for a whole 2.4 seconds, dramatically, and asks if Magill’s testimony is that she “will not answer yes.” Magill replies with her original answer, from line 4, that anti-Semitic speech becomes harassment when it becomes “conduct” (lines 21, 23-24). Now Stefanik pounces, possibly seeing an opportunity that she passed up on earlier, asking if that conduct means “committing the act of genocide” (lines 25-26)– loudly, with her pitch rising even further and her voice quavering on “genocide” (indicated by the tildes).

Obviously, this is not the “conduct” Magill had in mind, but she must be too stunned to respond because there is a 1.3 second pause before Stefanik continues. Stefanik then offers Magill “one more opportunity for the world to see your answer,” as if Magill is in a position to change it now. “Does calling for the genocide of Jews violate Penn’s code of conduct when it comes to bullying and harassment, yes or no?” (lines 29-32). After another long pause, Magill resists the terms of the question again in line 33, and Stefanik replies “the answer is yes” (though it obviously was not, as a description of Penn’s policies) before turning her withering attention to Harvard’s president.

An additional point of interest: Stefanik’s and Magill’s talk overlaps in lines 5-6, 18-19, and 21-22, as indicated by the square brackets. In all three cases, Magill repeats her words once she’s in the clear: the overlapping word in line 6 is repeated immediately afterward, the overlapping words in line 19 are repeated in the beginning of line 21, and the overlapping words at the end of line 21 are repeated in line 23. This is a well-known way of recovering from a momentary breakdown of turn-taking (Schegloff 1987), and indicates that Magill believed that, during the periods of overlap, it was Stefanik who properly held the floor.

Though it’s not captured in the transcript, Magill had an unfortunate habit of smiling when responding, possibly in the attempt to seem patient and benign but it made her seem condescending and faintly entertained by the whole ordeal. (This seems harsh, but watch the video.)

Magill was forced to resign a few days later and elite universities were widely faulted for falling back on free speech arguments in defense of the speech of pro-Palestinian protesters when their own track record on free speech/censorship was seen as very inconsistent.

Let’s return to Boden and Molotch’s article. Stefanik made a show of setting bounds on what would qualify as an acceptable answer, in lines 3, 22, and 32, when she says “yes or no.” However, this seems less a strategy for getting Magill to respond accordingly than a way of setting her up to fail at exactly that, and to take her to task for the highly qualified answers she has to give instead. Sometimes the power to shape public perceptions comes from making people respond in a certain way, and sometimes it comes from giving them a slightly longer leash and then faulting them for what they do with it.

Cited

Heritage, J.C., and D.R. Watson. 1979. “Formulations as Conversational Objects.” Pp. 123-62 in Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, edited by George Psathas. New York: Irvington Publishers, distributed by Halsted Press.

Molotch, Harvey L., and Deirdre Boden. 1985. “Talking Social Structure: Discourse, Domination and the Watergate Hearings.” American Sociological Review 50 (3): 273-88.

Raymond, Geoffrey T. 2003. “Grammar and Social Organization: Yes/No Interrogatives and the Structure of Responding.” American Sociological Review 68 (6): 939-67.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1987. “Recycled Turn Beginnings: A Precise Repair Mechanism in Conversation’s Turn-taking Organisation.” Pp. 70-85 in Talk and Social Organisation, edited by Graham Button and John R.E. Lee. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters.

Leave a comment