On May 15, 2025, the Supreme Court heard its first but perhaps not final case about birthright citizenship in the Trump era. The issues presented were about the power of district court judges to issue nationwide injunctions, which several did in response to an executive order by the president undoing birthright citizenship for the children of illegal immigrants. The merits of the constitutional argument were mostly sidelined by this procedural question, though the justices clearly expect to consider those at some point in the future.

Three advocates appeared. On Trump’s side was John Sauer, the U.S. Solicitor General (and the president’s personal attorney). Opposing him were Jeremy Feigenbaum, the solicitor general of New Jersey who represented assorted states and cities, and Kelsi Corkran, arguing on behalf of private individuals claiming injury from the executive order.

There’s much of interest in the arguments from a rhetorical perspective, including Sotomayor’s attempts to liken Trump’s executive order about birthright citizenship to an imagined order confiscating everyone’s guns and Justice Kavanaugh’s crediting all presidents issuing executive orders with “good intentions.” However, such rhetorical moves don’t easily lend themselves to a conversation-analytic (CA) treatment. This is because CA mostly focuses on how people deal with immediate interactional exigencies whereas rhetoric is often pre-planned and/or appears in the depths of long speaking turns which are essentially monologues.

Thus, I start with something more familiar to CA, and more in the spirit of this blog, namely interruptions, though this will bring me back to rhetoric quickly enough. Supreme Court advocates are provided with a Guide for Counsel which is very specific about interruptions: “Never interrupt a Justice who is addressing you. […] If you are speaking and a Justice interrupts you, cease talking immediately and listen.” In short, advocates may not interrupt justices but justices may interrupt advocates. These rules are aspects of what conversation analysts call the speech-exchange system (Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson 1974). While they are not always followed, justices do, indeed, interrupt without hesitation while advocates do so only occasionally. Also, advocates do mostly stop talking when they are interrupted, per the second rule. But not always.

The term “interruption” is not unproblematic. This is “in the first instance a vernacular term,” Emanuel Schegloff writes (2002: 301), “a term of vernacular description in the practical activity of ordinary talk,” one we often use while complaining that someone has cut us off before we can finish what we meant to say. The challenge is giving it a technical meaning that can be applied by an analyst lacking access to what a person “meant to say.” Here’s the definition I’ve used (Gibson 2005): an interruption is when one person is talking and another begins talking and then, in the midst of this state of overlapping talk, the first stops talking though their remark is “hearably incomplete.” For instance, if an advocate says “the fourteenth amendment grants citizenship to all children born in–” and then is cut off, it counts as an interruption, because the location of birth was obviously forthcoming. Interruptions can be successful, as in that example, or unsuccessful, if the initial speaker persists in finishing his or her point before yielding the floor. Note that “interruption,” under this definition, includes instances when the second speaker finishes the first’s sentence or otherwise does something supportive. These aren’t my ideas: Zimmerman and West (1975) basically operationalized the term this way many years ago.

There’s been some important research on interruption during Supreme Court oral arguments. Jacobi and Schweers (2017), for instance, analyzed several years’ worth of official transcripts, identifying interruptions by searching for lines that ended with “–“. While this operationalization, and their heavy (but not total) reliance on the official transcripts, wasn’t ideal, none of my reservations would explain away their quantitative findings. One is that female justices are particularly apt to be interrupted by both male justices and male advocates; another is that conservatives are more likely to interrupt liberals than vice versa. (Distinguishing gender and ideology effects is hard, however, as the female justices have mostly been liberal.)

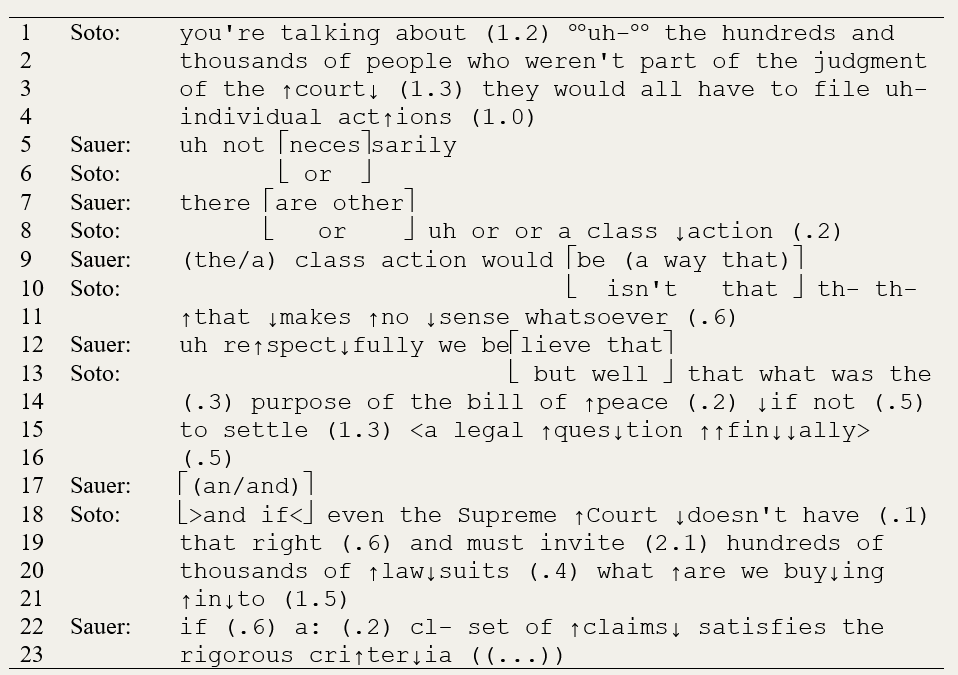

First to question Sauer was Justice Thomas. Then came Justice Sotomayor. Sotomayor’s questioning was striking because there was a period when she repeatedly asked a question and then interrupted Sauer as soon as he began answering. This is captured in the excerpt below, which occurred a couple of minutes after she started her questioning. (Each of the three excerpts comes with an audio clip which I recommend listening to. CA transcriptions aren’t perfect and mine were produced on an accelerated timeline. They’re explained here and I’ll also explain the most important conventions when they are relevant.)

The topic here is what legal recourse people affected by the executive order would have if it went into effect, excluding those who were parties to cases decided by a district court judge. First Sotomayor asks if they would have to “file individual actions.” Sauer begins to answer in the negative when Sotomayor interrupts him (in lines 7-8), seemingly to anticipate his answer, that affected persons would have recourse to a class action. (The brackets indicate overlapping talk.) This counts as a genuine interruption per my earlier definition because “there are other” is obviously incomplete. Sauer begins to affirm this in line 9 when Sotomayor interrupts him again. Here something curious happens. She says “that makes no sense whatsoever” (lines 10-11), but the referent of “that” is ambiguous, and given what follows, I think she might be referring to the words she had just put into his mouth, that “they would all have to file individual actions.” If that’s right, it suggests that she interrupts him in line 10 in order prevent him from affirming that there would be a class action alternative, exactly so that she can characterize his position as making “no sense.”

Sauer begins to resist in line 12 when she interrupts him for a third time. The bill of peace was a precursor to modern class action, rooted in English law, and the personal respondents argued, in their brief, that this showed that there’s a long history of granting relief to whole categories of people, including those who don’t show up in court, one that pre-dates nationwide injunctions. Justice Thomas asked Sauer about it a few minutes before, so it was very much “in the air” (like “oceans” in my post about the Trump-Zelensky altercation). In lines 13-15, Sotomayor observes that the point of that was to provide an alternative to everyone having to file individual suits. Sauer tries to respond in line 17, when it seems Sotomayor has finished her point (so that he won’t be heard as interrupting), and is interrupted a fourth time. In lines 18-21, Sotomayor again warns of the prospect of countless individual lawsuits were the courts unable to issue rulings protecting whole classes of people, concluding with “what are we buying into?” (were the Court to rule in Sauer’s favor). After a fairly long 1.5 second pause (appended to the end of Sotomayor’s turn in my transcription), Sauer responds, tentatively, as if unsure whether he’ll actually be permitted to continue.

A funny thing about this exchange is that while Sotomayor keeps interrupting Sauer, she is almost leisurely in making her own points, as if toying with him; note all the pauses in her talk, in parentheses and timed to the tenth of a second. Even by the standards of Supreme Court justices, this is extreme, and a minute later when Sotomayor interrupted him again Chief Justice John Roberts testily asked “Can I hear his answer?”

Also interesting is that Sotomayor repeatedly interrupts and then, finding herself speaking “in the clear” (i.e., no longer in overlap), restarts her sentence differently. This happens twice, in lines 10-11 and 13, as if her decision to interrupt slightly preceded her plan about what to say once she did.

After the excerpt, the two continued talking about this, with Sauer touting class action as a solution and Sotomayor skeptical of that—and with reason, as Sauer later suggested that it might not apply to the people affected by this executive order. During this, Justice Roberts tried several times to interject and eventually succeeded in wresting control of the floor from his female colleague by interrupting her.

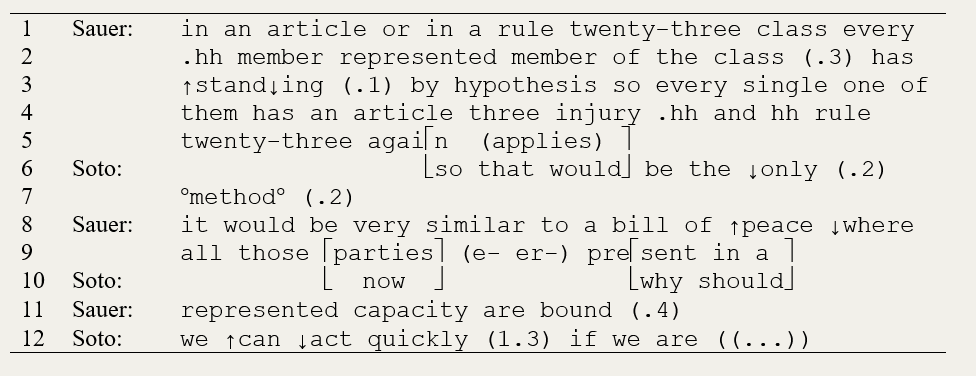

The next time Sotomayor spoke was during seriatim, which is when the justices take turns asking their final questions by order of seniority. (This was a pandemic-era innovation, and it’s what turned Clarence Thomas, who once went an entire decade without asking a question, into an active participant.) This time, Sauer took a different approach to Sotomayor, persisting when she tried to interrupt, at least long enough to finish his sentences.

At 31:36, transcribed above, Sauer is again talking about class action, as governed by Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedures. In line 6, Sotomayor begins speaking in overlap. This could be considered an attempted interruption but it’s clear what he’s in the process of saying, and it’s likely that he’s only a word or so away from finishing his point, so this is considered a lesser turn-taking infraction (Jefferson 1983). “That would be the only method,” she asks. (We consider this a “declarative question” even if it is not a grammatical one.)

In lines 8-9, Sauer responds by likening a class action to a bill of peace. Sotomayor tries to interrupt (in line 9) but Sauer persists, finishing his point in line 11 in the clear, though this means violating the Guide’s second rule. Note that when Sotomayor responds in line 12, her turn beginning once again bears little resemblance to the words she used when she attempted to interrupt: in overlap she said “now why should” and now she says “we can act quickly.” As earlier, it seems that her decision to interrupt precedes, by some milliseconds, a concrete speech plan for what she’ll say upon succeeding (see, relatedly, Levinson and Torreira 2015).

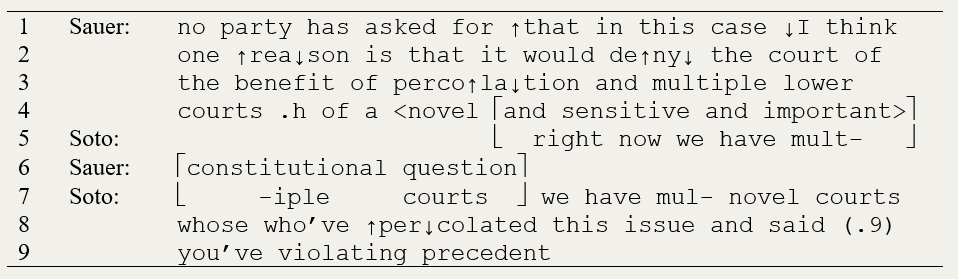

Now for the final segment, starting at 34:13 (above). Sauer argued that the whole birthright citizenship issue needed to “percolate” in the lower courts for a while longer before being considered properly by the Supreme Court. (This is related to the question of whether a controversy is “ripe” enough for judicial intervention.) He’s making this point when Sotomayor interrupts in lines 4-5. Again, he persists to the end of his point, though now completely in overlap with the justice, as his “and sensitive and important constitutional question” overlaps with her “right now we have multiple courts.” Once he’s finished, Sotomayor restarts her response (line 7), a well-known practice when one emerges victorious from overlap (Schegloff 1987), with the exception of swapping “multiple” with “novel” in line 7 (though this might have simply been a mispronunciation of the word).

The takeaway? The Court’s rules favor justices when it comes to interrupting, and they may use this to rhetorical effect, to prevent an advocate from saying something that would dilute or distract from the point the justice wants to make. For their part, advocates have to put up with this, which makes it especially interesting when they do not, either by interrupting a justice or, here, by not immediately backing down, either because their point is too important to abandon or because of their experience with that particular justice.

Cited

Gibson, David R. 2005. “Opportunistic Interruptions: Interactional Vulnerabilities Deriving from Linearization.” Social Psychology Quarterly 68 (4): 316-37.

Jacobi, Tonja, and Dylan Schweers. 2017. “Justice, Interrupted: The Effect of Gender, Ideology, and Seniority at Supreme Court Oral Arguments.” Virginia Law Review 103 (7): 1379-486.

Jefferson, Gail. 1983. “Notes on Some Orderlinesses of Overlap Onset.” Tilburg Papers in Language and Literature 28: 1-28.

Levinson, Stephen C., and Francisco Torreira. 2015. “Timing in Turn-taking and its Implications for Processing Models of Language.” Frontiers in Psychology 6 (article 731).

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. “A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation.” Language 50 (4): 696-735.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1987. “Recycled Turn Beginnings: A Precise Repair Mechanism in Conversation’s Turn-taking Organisation.” Pp. 70-85 in Talk and Social Organisation, edited by Graham Button and John R.E. Lee. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters.

—. 2002. “Accounts of Conduct in Interaction: Interruption, Overlap, and Turn-Taking.” Pp. 287-321 in Handbook of Sociological Theory, edited by Jonathan H. Turner. New York: Kluwer.

Zimmerman, Don H., and Candace West. 1975. “Sex Roles, Interruptions and Silences in Conversation.” Pp. 105-29 in Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance, edited by Berrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Leave a comment