On Friday, February 28, 2025, President Donald Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky met in the Oval Office in front of the press corps to describe Trump’s efforts to simultaneously sign a deal with Ukraine for rare earth minerals and bring the war with Russia to an end. The full video recording is above. Though Trump took several opportunities to criticize his predecessor, the first forty minutes were mostly civil, with Trump repeatedly praising Ukraine’s fighting forces even while he portrayed himself as a neutral arbiter between the two countries who mainly wanted to bring the conflict, and the killing, to an end. For his part, Zelensky insisted on the need for security guarantees, and only really challenged Trump once, for the latter’s depiction of Ukraine’s cities as decimated by the war. Zelensky also described Putin as a “killer and terrorist,” who hates Ukraine and who is unreliable as a negotiating partner given the ceasefire agreements he’s broken in the past.

Things went south around the 42:20 mark, however, eventuating in a “shouting match” (though only one side shouted) between the two presidents, with Vice President J.D. Vance adding fuel to the fire and arguably starting it to begin with. (I strongly recommend clicking the link to watch the video if you haven’t seen it.) CNN reported that “seasoned diplomatic observers” viewed this as a “political mugging, a trap set by the Trump administration to discredit the Ukrainian leader and remove him as an obstacle to whatever comes next.”

Conversation analysis (hereafter, CA) is the study of naturally occurring talk. While CA originated with the study of mundane conversation, it’s no less relevant to the study of talk in institutional settings, including in high-stakes political venues. My own work on the deliberations of President John F. Kennedy and his advisors is one example (Gibson 2012); my work on Supreme Court oral arguments (which is ongoing) is another (Gibson 2024).

What light does CA shed on this heated exchange? Many seem to assume this was a set-up, but I want to approach the data naively, to ask what the evidence for this is, or, alternatively, to formalize whatever intuition people bring to bear when they reach that conclusion.

Let’s start with the ordinary rules of turn-taking. One builds on the idea of an adjacency pair, which is a two-turn sequence in which the first creates a firm expectation for the second. For example, someone asks a question and the recipient answers it. One turn-taking rule is that the recipient of a question (or request, compliment, proposal, etc.) speaks next so as to respond. A second rule is that when no one is selected as the next speaker, the first person to begin talking (upon plausible completion of the previous speaker’s turn) gets the floor (Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson 1974). These two rules normally uphold the higher-level one-speaker rule, except on the margins of speaking turns when one person begins speaking a bit before the previous speaker has finished – though, to be sure, there are cultural differences (Tannen 1985). Putting those aside, there are also procedures for restoring one-speakership when it’s broken down (Schegloff 2000), and these are generally effective. Consequently, the sustained overlapping talk begs for explanation.

One possibility is that neither side wanted to be seen as passively accepting the other’s characterization of the war, especially in this era of soundbites and video clips, except that they had been content to let each other speak mostly uninterrupted prior to the blow-up.

Another possibility is that Trump and Vance planned to attack Zelensky, to accuse him of insufficient gratitude, and either were willing to risk the shouting match or actually welcomed it. One kind of evidence of planning is inapposite utterances – things that don’t quite make sense at that moment, particularly vis-à-vis the immediately prior talk of the other side. Another is especially smooth coordination between the members of one “team” (Goffman 1959), if planning reached the level of “you say X and then I’ll say Y.”

Relevant to the planning hypothesis is the fact that this exchange started right after Trump asked for “one more question” (39:54), so at what he imagined to be the end of the meeting. But I’m not sure what to make of that, beyond the fact that it may have forced Trump and Vance to take as their provocation something from Zelensky that wasn’t particularly provocative, lest they lose the opportunity entirely.

A third possibility is that this was not planned, and that what happened was that Zelensky said something that was genuinely triggering, more so than anything he’d said previously, and this could not be allowed pass, even for a moment. But while this might explain why Trump was initially provoked, it is not sufficient to explain the so-called shouting match. For that, we need to explain Zelensky’s behavior as well, of talking while Trump was talking. It takes two to tango, and two to talk over each other. He, too, may have planned, specifically to hold his ground if attacked, or he might have found himself suddenly abused at a level that demanded an immediate response.

What is clear is that any sustained breakdown in turn-taking bespeaks a greater commitment to talking, and to the goals that can only be pursued by talking, at this very moment, than to maintaining order and the veneer of civility (Schegloff 2000). The question is whether the episode is self-explicating, with each move a recognizable response to the prior one, or inexplicable without appeal to (on the Trump/Vance side) a plot to make these particular accusations.

Let’s make our way towards the first excerpt, capturing the first thirty-four seconds of the so-called shouting match. Immediately before the start of this, Vance, who had mostly been quiet, spoke up in support of Trump’s call for diplomacy, faulting Biden for unproductive bluster. Zelensky then addressed Vance directly, recounting Putin’s perfidy in earlier negotiations. “What kind of diplomacy, J.D., are you speaking about?” (Why he addressed the VP by his first name, I don’t know.) On the spot, Vance switched gears, claiming that Ukraine was forcing conscripts to the front line and berating Zelensky for trying to “litigate this case in front of the American media” rather than thanking Trump for trying to end the conflict. Vance then accused Zelensky of both taking visitors to Ukraine on a propaganda tour (after Zelensky faulted the VP for never having visited) and, again, of being insufficiently respectful of Trump. During this, turn-taking was strained but maintained as Zelensky repeatedly yielded to Vance. Zelensky, finding himself bombarded with “a lot of questions” asked for Vance’s permission to “start from the beginning.” Vance gave him the go-ahead, and not grudgingly.

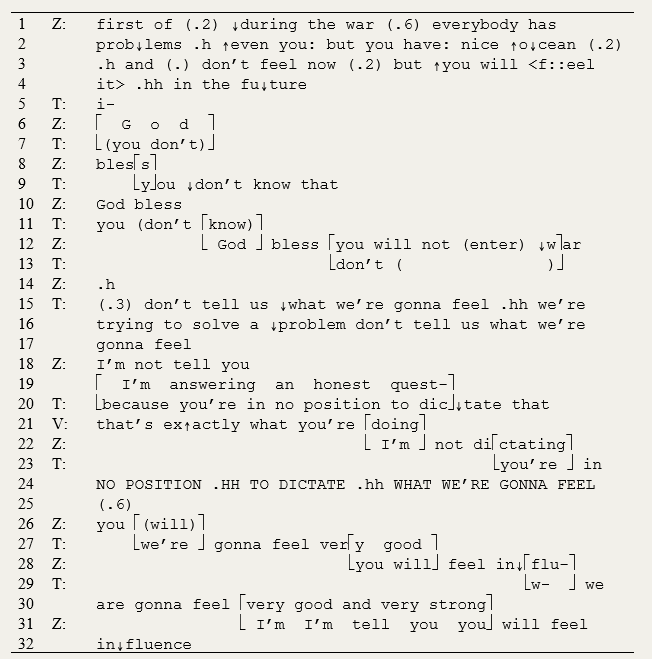

This is where the first excerpt begins. Conversation analysts like the minutiae of talk, such as the length of pauses, the precise start and stop of overlapping talk, and changes in pitch and volume. These are important details because this is what talk largely consists of, though it’s typically lost when people are quoted in print. That is, if our goal is to explain what happens in a conversation (a loose term for which CA has no great alternative), we need to carefully represent what happens, as well as the immediately previous talk that helped bring it about and ideally also immediately subsequent talk which often provides direct evidence of what the parties involved think just happened (the so-called next-turn proof procedure). You’ll almost never find a conversation analyst analyzing a cleaned-up transcript, which is why I had to wait until the tape recordings from the Cuban missile crisis were released before I wrote my book (Gibson 2012), though transcripts were published earlier (May and Zelikow 1997). (I was forced, however, to rely on minutes from meetings that were not recorded, and later wrote about how such minutes are created (Gibson 2022).)

Years ago, Gail Jefferson created what is now known as the Jeffersonian transcription system, which I mainly follow. (That’s explained here, but the conventions relevant to my analysis are also explained below, when they’re relevant.) This is not perfect, and the analyst has a lot of discretion in deciding which conventions to use and how far to push them, and even an extremely detailed transcript is only a crude representation of the original recording, to which the analyst should frequently return. At the same time, a transcript supports sustained analysis of the kind that is difficult when we just listen to a recording: there are some things about talk that are only evident once talk is no longer heard, but instead inspected in print.

One more thing: CA was born at a time when audio recordings were easily made but video much less so. This is one reason that so much published CA focuses on verbal communication, at the expense of whatever was happening nonverbally. Another reason is that it is very hard to translate visual behavior to the written page, for while mostly one person speaks at a time, everyone is emitting nonverbal signals continuously, with every part of their body. A third reason is that there are a lot of identifiable regularities on the verbal level, enough so that conversation analysts are able to make new discoveries while focusing just on that. It’s also why people are not entirely flummoxed when they talk on the telephone: talk largely structures talk. All that said, there is a lot of important research happening right now incorporating nonverbal behavior (e.g., Mondada 2019).

Now for the excerpt, this time for real. Zelensky starts by observing—in somewhat imperfect English—that wartime always brings problems. Then he does something that proves provocative, predicting that the U.S. will “feel” those in the future. This seems unnecessary, but the reference to the “ocean” is telling, for this is something that had come up repeatedly earlier, after Trump suggested that this gave the U.S. less of a stake in the conflict than Europe. Here it seems Zelensky feels compelled to return to it, in the attempt to make the aforementioned “difficulties” into something more than a Ukrainian problem. But it proved to be a bad move. Trump immediately objects: “you don’t know that” (line 9). It’s possible that Zelensky’s prediction genuinely provoked Trump, by foretelling a future incompatible with the latter’s MAGA optimism. However, Zelensky had earlier predicted that American troops might get drawn into the conflict, without objection from Trump, so this may instead be evidence that Vance’s challenge a moment earlier primed Trump to respond differently than earlier to a dark prediction. Or maybe it announced that it was time to get the planned assault underway. Zelensky’s initial response is to basically ignore Trump and indeed talk over him—the square brackets indicate overlapping talk—in order to hope, aloud, that the U.S. will not “enter the war.” (The word “enter” is in parentheses as I’m not 100% sure this is what he says.)

Trump then turns this prediction about how the U.S. will feel into a demand: “you’re in no position to dictate that” (line 20). This construes Zelensky’s prediction as a demand, and is an even clearer clue that that Trump was looking for some pretense to go on the attack. Zelensky tries to defend himself, saying that he is just trying to answer an honest question (line 19) from Vance, but the VP gives him no aid, backing up Trump in line 21. Zelensky tries again in line 22, but is interrupted by Trump, who in line 24 repeats his accusation, that Zelensky is dictating, now in a raised voice (as indicated by the capitalization). Zelensky does not back down, however, gently predicting that the U.S. will feel “influence” – though this is such a weak prediction that one wonders if he it’s what he originally had in mind. Trump is talking at the same time, offering the competing prediction that “we are gonna feel very good and very strong” (lines 30-31). As a response, however, this is peculiar: though its optimism is very much in character for Trump, this doesn’t seem crafted to be particularly germane to any specific interpretation of what Zelensky was actually predicting.

Things quickly escalate further, as seen in the second excerpt, capturing the next thirty seconds. Still almost yelling, and then definitely yelling by line 58 (in bold), Trump chastises Zelensky for his “bad position,” which then evolves into “you don’t have the cards,” and then into the accusation that Zelensky is “gambling with World War III,” something he repeats. Zelensky protests softly throughout, but only once does Trump indicate that he’s listening: in line 48, speaking in overlap, Zelensky says “I’m not playing cards,” to which Trump responds (after a slight processing delay): “no, you’re playing cards.” At the end of the excerpt, Trump picks up Vance’s earlier accusation of disrespect.

This was the climax, drama-wise, but the painful exchange continued for a while longer along the same lines (except with a greater concentration of digs against Biden), before Trump brought it a close, announcing “this is gonna be great television.”

What can we conclude from all of this? It seems that, minimally, Trump was prepared to go into attack mode, and had certain lines at the ready: that Zelensky was too demanding, he didn’t have the cards, that he was risking a larger war. For his part, Zelensky’s responses were softly articulated and generally respectful (which is why many dislike calling this a shouting match), yet he persisted in them even when Trump was talking, apparently thinking that he could ill afford to be passive while he was being so publicly abused. What he clearly could not do was use the occasion to praise Trump, which would have been seen as abject groveling. The immediate result was the widespread perception that Zelensky had made an awful blunder in allowing himself to be baited, but it doesn’t seem like Trump and Vance actually needed him to take the bait to find an excuse to browbeat him. However, the Ukrainian president’s resistance, mild as it was, may have been what was needed to turn this into a full-scale blow-up.

Emanuel Schegloff, one of the founders of CA and the source of so many of its foundational insights, once wrote that sustained overlapping talk suggests, for participants and the analyst, “some sort of greater interactional moment or investment for the parties, either proximately interactional (such as needing for various reasons to get something said in that turn position) or representing more distal and even symbolic matters, such as ones of deference, standing, and so forth” (Schegloff 2002: 293). There’s nothing that creates “greater interactional moment” than TV cameras, when speakers are aiming to make an impression upon the viewing audience.

Some later additions

- Alexa Hepburn offers an independent but largely commensurate analysis here.

Works cited

Gibson, David R. 2012. Talk at the Brink: Deliberation and Decision During the Cuban Missile Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

—. 2022. “Minutes of History: Talk and its Written Incarnations.” Social Science History 46 (3): 643-69.

—. 2024. “Hyping the Hypothetical: Talk and Temporality during Supreme Court Oral Arguments.” Qualitative Sociology 47 (2): 249-79.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor-Random House.

May, Ernest R., and Philip D. Zelikow (Eds.). 1997. The Kennedy Tapes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mondada, Lorenza. 2019. “Contemporary issues in conversation analysis: Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 145 (47-62).

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. “A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation.” Language 50 (4): 696-735.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2000. “Overlapping Talk and the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation.” Language in Society 29 (1): 1-63.

—. 2002. “Accounts of Conduct in Interaction: Interruption, Overlap, and Turn-Taking.” Pp. 287-321 in Handbook of Sociological Theory, edited by Jonathan H. Turner. New York: Kluwer.

Tannen, Deborah. 1985. “Silence: Anything But.” Pp. 93-111 in Perspectives on Silence, edited by Deborah Tannen and Muriel Saville-Troike. Norwood: Ablex.

Leave a comment